How I Lost My Backpack with Passports and Laptop

A tale about mixing GABAergics, neuroticism, responsibility and Heidegger

“It's only after we've lost everything that we're free to do anything.” I hadn’t lost everything — just my backpack with two passports and my laptop — so I became only a little freer.

This story happened three months ago. It is an embarrassing story. It is embarrassing and difficult to tell — but that's exactly why I'm telling it to you.

***

Sunday morning. I woke up at a small table in the entrance hall of some house in London — no idea which one, but definitely not mine. The last thing I remembered was leaving a party at my friend's café, very drunk.

A resident walked past me and said "Hi." I walked to door number four and asked him:

— How do I sleep?

— Sorry?

— Sorry!

Approaching a random apartment door and asking in broken English how I could sleep there was definitely not part of my morning plan that I devised the previous evening. A wave of shame boiled away the last remnants of sleep. I bolted outside and wandered. The shame subsided quickly. And three minutes later, I spotted a street sign reading "Camden St" — it turned out I was in the eponymous London district, Camden, which I was pretty familiar with.

I found a bus stop and sat down. My back felt wonderfully light. After a few seconds, I realized what this sensation actually meant — and flinched: my backpack was gone.

A couple of years ago, I would have panicked at this moment. I'm pretty neurotic: my mind is constantly occupied with producing negative scenarios that "need" to be considered and anticipated. I eat myself from inside out with endless "what ifs", calculating worst-case scenarios and failures — all that sort of thing.

But for the last couple of years, I've been fighting these tendencies. I consider it a big achievement that I’ve — however clumsily — learned to let things ride instead of over-controlling them. So I decided: you're playing a game called life, but on a pirated CD copy with cutscenes stripped out to save space. A new level has just been loaded, “Find a Backpack”, but they didn't show you the cutscene (god damn pirates cut it out!). Worrying about how it happened is pointless — that part is outside your control.

And anyhow: I probably just left the thing at the party. After all, I'm a grown and responsible adult — and not some moron who could lose a backpack while drunk.

I headed to my friend's place. On my way I stopped and ate a Polish hot dog at Camden Market — they are awesome there. After arriving at the right station, I also grabbed a cupcake for dessert from a kiosk — and then continued to my friend's place in excellent spirits.

When the backpack wasn't at my friend's place, I tensed up. At the nearest police station, they told me that the police don't deal with lost property: now if my backpack had been stolen…

***

I hadn’t been blackout drunk in 17 years — since my teenage days. I was sixteen and sad. For these two reasons, I drank a bottle of cheap brandy mixed with tea and went to see my then-girlfriend. The bottle of brandy turned out to be a little too much, and everything after that is a blur.

My head was resting on her lap, her legs sheathed in dark nylon tights. I was experiencing a hitherto unknown form of affection, periodically vomiting into a plastic bag that happened to contain two graduation photo albums — mine and a classmate’s. My album absorbed most of the damage, while my classmate's only got somewhat splashed. Later I told him I’d accidentally spilled some tea on it. Technically true: it was tea mixed with brandy — after a short stop in my stomach.

***

Back then, I was mixing tea with cheap brandy. And this time, fifteen years later — I was mixing alcohol with phenibut. Do not mix alcohol with phenibut. Or at least mix it more carefully than I did!

Phenibut is a nootropic that was originally developed in the Soviet Union. It is currently sold in pharmacies in Russia and some ex-USSR countries — formally by prescription, but in half the cases, they'd sell it to you without one.

In the UK, where I currently live, phenibut is unregulated. I order it in large black ziploc bags from a perfectly legitimate company that even itemises the exact amount of Value Add Tax it remits to His Majesty’s Revenue & Customs.

In higher doses phenibut is a semi-recreational substance reminiscent of alcohol. But while alcohol tends to "wreck you," phenibut "enhances sobriety," increasing the clarity of mind. Phenibut is a gentle social lubricant that doesn’t cloud your consciousness. It relaxes you a bit, reduces anxiety and improves well-being. And most importantly: it makes socializing easier.

And for me phenibut is more than just a social lubricant. It’s also a psyche-recalibration tool.

There's a way of dealing with anxiety called exposure therapy. According to psychologists, it's effective for all levels of anxiety: from full-on panic attacks to mild worry. Here’s how it works. Instead of talking circles around your fears and overanalysing your childhood memories, you dive headfirst into your worst nightmare (or a mid-level fear, depending on the level of your anxiety). Take the fear of public speaking as an example: you're afraid to go on stage, your knees are shaking, your head is spinning, the whole package. But you step on stage, freak out, survive; the psyche logs “oh, still alive” — and the fear shrinks a notch. Rinse and repeat, and the fear gradually fades away.

Phenibut lets you pharm-hack this process. Take it a couple of hours before the scary situation and you arrive there not riddled with anxiety, but in a state of relative calm. The psyche registers “everything’s alright” and softly updates its emotional patterns. This kind of exposure works faster and gentler.

And this hack isn’t only psychopharmacological — it’s psychosocial as well. Using the same public-speaking example: with phenibut you walk on stage relatively calm and not freaking out — the audience reads your confidence and reacts differently. I'd even go as far as saying the following: phenibut indirectly modulates the emotional state of people around you — as a sort of a "+3 charisma" potion.

A personal example. I’m doing standup now — I’ve had about 60 performances over the last few months. But when I first started performing stand-up, I’d sometimes get so nervous that I’d feel like throwing up. Eminem’s lines resonate with me much more vividly: "His palms are sweaty, knees weak, arms are heavy. There's vomit on his sweater already, mom's spaghetti." Phenibut helped a lot!

Now I’m going to talk about alcohol. Alcohol is a mediocre drug, a standard social lubricant in most cultures. It dulls the sharpness of thought, numbs your feelings, and gives you a hangover the next morning. I am not going to spend much time here describing alcohol in-depth — you've probably tried it yourself and formed your own opinion on it.

Compared to phenibut, alcohol's receptor profile is wider and messier. For example, phenibut primarily acts on GABA— the main inhibitory subsystem of the brain. So does alcohol, but alcohol also blocks NMDA receptors (like ketamine and other dissociatives). I’ve barely touched alcohol the past year; and its mild NMDA antagonism just annoys me now. If I wanted dissociation I’d snort ketamine, dammit — and I haven’t wanted ketamine all year.

Phenibut has had a very positive impact on my life, allowing me to overcome many difficulties and anxieties. Besides helping with the fear of public speaking, phenibut also improved my sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic: sleeping on phenibut is very restful. Alcohol… My attitude toward alcohol has swung back and forth like a sine wave like four times over the course of my life — from quite negative to generally positive. It’s too ambiguous a drug.

Yet I must admit that alcohol has a certain a e s t h e t i c. Other substances work in such small doses, that you take them as powders, pills, tabs, and solutions — as if you were a disembodied clump of consciousness, only accidentally trapped in the prison of a meatbag. Alcohol — whether it's a cheap beer, a glass of single-malt, or an overpriced negroni — is something you consume as a material being with the full richness of bodily experience, fully integrated into the real world.

Alcohol is everywhere: bars, pubs, social events. It’s the default drug of our culture. So: do not mix phenibut with alcohol. Or at least mix it more carefully than I did! Both substances are GABAergic, which means they potentiate each other. For a long time I scrupulously followed my own advice, but then I became a less neurotic kind of a cowboy and started ignoring it — what’s the worst that could happen?

What, besides losing a fucking backpack.

***

"Cowards die many times before their deaths; The valiant never taste of death but once." The day after losing my backpack, I was dying thousands of deaths.

In my backpack there was some phenibut which, although legal, looks like a bag of white powder. Luckily, it was in a black zip bag with the company logo and the word "phenibut" on it. But in addition to phenibut I also had scales which were possibly used to handle substances of potentially reduced legality. Someone could find my backpack, turn it in to the police — what if they find traces! Rationally I knew the UK doesn’t care much about personal-use quantities of drugs, let alone microscopic traces of them, yet my neurotic mind painted vivid scenes of retribution — as if I’d left a suitcase full of cocaine bricks at the border.

For my ADHD, I'm officially prescribed lisdexamfetamine — a Schedule II stimulant. Due to my sensitivity to stimulants I take it daily in doses below the smallest licensed capsule, which means dissolving a capsule in water and measuring the solution with a syringe. So I usually carry a little vial of diluted medication with me along with a couple of measuring syringes — no needles of course, yet the kit still looks vaguely junkie-ish. And of course, of course, my mind painted pictures of retribution for this too.

The thought that someone might rummage through my laptop, my files, and dozens of services I'm logged into was also very unpleasant. Yes, I logged out of the most important ones pretty much immediately, and most likely anyone who found it would simply wipe the laptop clean before selling or using it — but once you start worrying, you have to worry in full force, right?

A reader of this essay might say: “You’ve previously told us about how you cut down your neuroticism! Sounds like you're all talk and no action.” To that reader, I’d reply: sometimes all talk, sometimes quite a lot of action, and sometimes a perfect balance of both. I manage differently: badly, reasonably, and pretty well.

Neuroticism is an entire disposition of your mind towards reality, a recursive tendency at all levels to spin up negative scenarios and then think through them. Neuroticism is usually described as a set of high-level patterns and strategies, but it also manifests at the sublinguistic level, in the microstructure of your mind. After partially dealing with neuroticism at a relatively high level, you still need to defeat it at the level of micro-habits formed over thirty years. And that’s not a quick process.

So although I have reduced my neuroticism, it's only by half, or maybe even by just a quarter. Letting situations play out on their own is a skill I’m better at now — but I'm still very much working on it.

***

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger wrote that when you’re hammering, the hammer is not perceived as a separate object — an elongated piece of wood with a metal head on the end. Phenomenologically it functions as an extension of your body, dissolving into the act itself: driving the nail. While you’re swinging it, you don’t think about its weight, material, or shape. Only when the hammer breaks, disrupting the familiar pattern of use, does it suddenly present itself as a separate object made of wood and metal.

Heidegger used this example to illustrate two different modes of relating to things. First, readiness-to-hand (German: Zuhandenheit) — the instrumental mode in which the tool fuses with intention through practical use. Second, presence-at-hand (German: Vorhandenheit) — the analytic stance in which the tool shows up as an independent object demanding inspection and analysis. Everyday items are woven into the context of practical activity, into the web of relationships and practices that constitute our world. A lost backpack isn't just lost property. It's a gaping tear in the fabric of habits.

My backpack held my five Tangle Teezer hair brushes — losing them wasn't so bad, but losing all five was. I used to only have two: one at home and one in the backpack. But with my ADHD, I’d constantly take the brush out of my backpack and forget to put it back. After getting thoroughly annoyed of this happening for the hundredth time, I decided that it's better to have five: a couple at home, a couple in the backpack — moving them back and forth. And one I specifically buried deep inside the backpack for a rainy day, so I wouldn’t be tempted to fish it out without cause. The scheme guaranteed anywhere from one to five brushes in my bag. And just before the party, I put all five there. I didn't have a single hair brush left at home, so I had to go buy a new one.

In my backpack there was a condom holder — a kind of "wallet" for condoms, a little “notebook” with five clear sleeves, each sized for a single condom. An item of sentimental rather than functional value: the additional convenience from it isn't that big, but I bought it almost fifteen years ago at my first work place. Losing it stung.

In my backpack there was a T-shirt from the Spanish town of Ajuy in the Canary Islands (pronounced “Ахуй” in Russian, an obscene word that roughly means “a state of utter flabbergastedness”). The print with the town's name on it was already worn off. So I wasn’t upset about the shirt itself — only about losing it for no real reason.

Most important of all: a 2021 MacBook. That was the item I worried about the most. It's not that new, and I quickly found out that a used or refurbished similar one could be bought for 500-600 pounds — far from a critical amount for me. But just as Heidegger’s hammer is more than wood plus metal, that laptop was more than an aluminium shell with a battery, screen and keyboard. The laptop was also the configured software and developed patterns of use. Losing it felt like losing a natural extension of my mind — a “bicycle for the mind”, as Steve Jobs put it.

Software can be installed on a new laptop, patterns can be developed, you get used to the keyboard and other hardware — but this process isn't instantaneous. In 1.5 weeks I was scheduled to host a dating show. Not an ordinary one, but a prediction-markets dating show. Participants come on stage, and the audience bets on who will end up liking whom. This is a rather technologically complex setup: right on stage, I need to create prediction markets with pairs of participants' names and project the audience's aggregated predictions on the screen behind them. I’ll publish a separate essay about the shows later; meanwhile the event description is here.

From the very beginning of this story, what gnawed at me was the prospect of hosting the dating show without my trusty laptop. I could stoically take battling inner neuroticism with all of its negative loops as an interesting psycho-practice that made me stronger. But the prospect of letting down fifty to a hundred people in the audience bothered me in a completely different way from the start. It wasn't a temporary inconvenience or an imagined scenario, but a real tangible problem that could affect other people.

Every second of delay on stage lowers the intensity of audience attention and the effectiveness of the show. Viewers would be under-entertained. Participants on stage would find their love with less probability — which is not a theoretical concern — I had two couples form as a result of previous shows. The stakes in this game are genuinely high!

What else did I lose? Oh right, my passports! Both my Russian and British passports were in the backpack (I have dual citizenship). Dear reader, I honestly couldn’t give a single fuck about them — I put the word passports in the headline purely for dramatic effect to lure you into reading this piece. The British one is easy enough to replace. The Russian one is pretty useless currently: I’m not planning a trip to Russia any time soon, and the British passport already gives me visa-free access to far more countries.

The backpack also held a parcel with the street address of my rented mailbox printed on it. The parcel itself was inexpensive and unimportant, so its loss even made me happy — the address on it gave me hope that someone would find my backpack and contact me. Recently having acquired my British citizenship I had faith in the society here. In Russia I’d rate my chances of getting the pack back as slim, but in the UK I pegged them to be 30-70%.

The dilemma: when do I stop hoping the backpack will turn up and just buy a new laptop? Wait too long — and I won't have enough time to get used to the new machine. Wait too little — and I might waste money if the old one suddenly reappears.

***

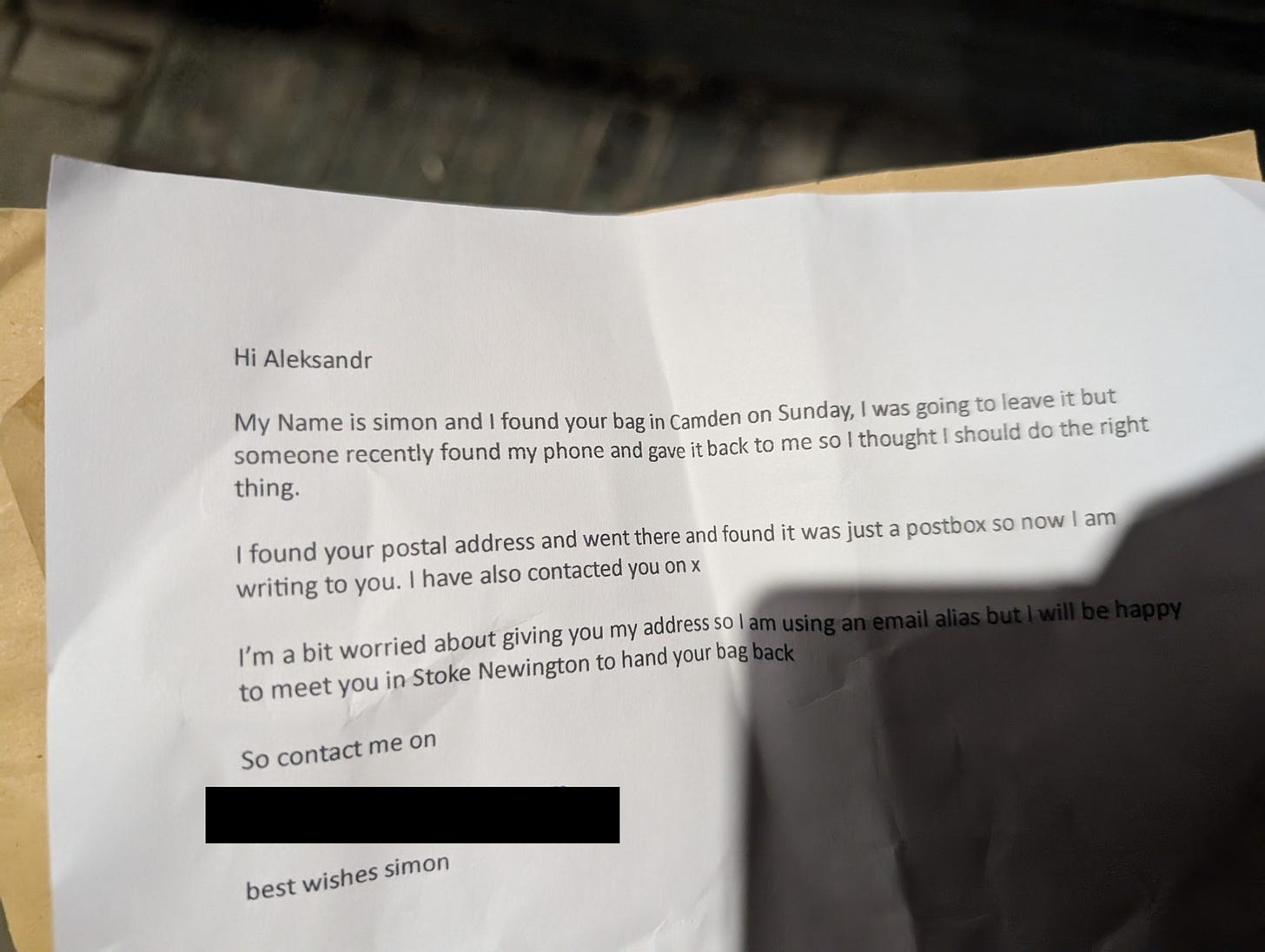

The very next day — two days after the loss — I received a letter to my mailbox address in London. A man named Simon wrote: he had found my backpack and wanted to return it. He’d spotted the bag in Camden and at first thought of walking past, but someone had recently returned his lost phone, so he decided to do the right thing. Social fabric in a high-trust society is structured in an interesting way: there is this sort of a domino effect — someone returned his phone, and he didn't leave my bag. Here's his letter in full!

We met in two days. Simon turned out to be a lean and handsome British man in his fifties — with silver hair and a pierced ear. He somewhat reminded me of Benedict Cumberbatch. Simon gave my backpack back to me intact.

I really wanted to thank Simon in cash and tried a handful of strategies for this. First, in our correspondence, I offered him £111 — deliberately an interesting non-round number to increase the chances that he would take the money. But he declined. Next I offered to donate the same amount to any charity of his choice — he declined again. At the meeting, I made one last attempt, holding cash right in my hand, but received the same friendly but firm "no".

Simon told me that he’d found my backpack lying in Camden near Amy Winehouse's house. When he asked how I’d managed to lose it, I gave him the short version: "It’s embarrassing to admit, but I got blackout drunk — this hasn't happened since I was seventeen."

***

"It's only after we've lost everything that we're free to do anything." I hadn’t lost everything — just my backpack with passports and a laptop — so did I get even a little freer? I think so. Sure, it would have been better not to lose the backpack at all, but since I did lose it — I should extract some lessons from this entire experience, right?

So what did I learn? In a roundabout way I was reminded about how decisive habits are. I felt how strongly the availability of everyday objects can affect my life — and how much time and energy drains away when you can no longer rely on your familiar patterns. I resolved to invest more effort in organising my personal space. And now every day I try to pick one small thing to improve at home: ordering a set of drawer organisers, deciding on the perfect place to store a pair of scissors, taking a mental note to buy a poster for the wall, and so on. I’m more deliberate about my environment now.

I spent these few days of the neurotic bad-trip-without-psychedelics observing and adjusting my internal strategies for adapting to uncertainty. And perhaps the most important takeaway here is seeing more clearly the difference between neurotic hyper-control/hyper-responsibility and real responsibility.

Hyper-responsibility isn't "too much responsibility," but an attempt to control what you can’t change or don’t own. A responsible person won't lose a backpack having lost a backpack, won't torment themselves from within with the burden of imaginary responsibility for what has already happened. They would focus on what can still be changed.

Same with projects: when you find yourself in new and worse conditions in a project, don't worry so much — adapt, and then "do what you must and come what may". Projects now go more smoothly! Less unnecessary control — more drive. And, paradoxically, more real effectiveness.

***

A week later, I went to another party at the same café. Last time, the owner threw a tropical-beach party, so I was surrounded by beautiful half-naked girls and boys. This time, the café was rented by a friend of mine for a party in honor of the Slavic god Veles — and once again I was surrounded by beautiful half-naked girls and boys (but different ones). And my backpack was back with me — oh, what a stressful week it had been!

A similar party in the same place. Of course, I took some phenibut. And of course, there was alcohol at the party. Fate was testing me, no doubt.

The final test — close to the end of the party I grabbed a bottle of Corona Extra. Its glass chilled my palm in a pleasant way. That bitter-sweet beer taste was calling to me, but flashbacks of the lost backpack kept poking at my mind. "Inside each of us, there are two wolves fighting," one loves to drink, and the other one loses backpacks... wait, no — it's the same single wolf. I took another look at the bottle — and I clearly felt that alcohol was not the most healthy and benevolent force in my life. In fact, it was probably a rather harmful force. So — perhaps the core lesson of this story is not to drink alcohol. Or at least not to mix alcohol with phenibut.

But I decided that I would learn these lessons some other time. And this time, I would show fate how well I had learned the lesson of flexible self-restraint and moderation. I opened the bottle with a clear intention not to get too drunk. And for the next couple of hours, I drank a few bottles sip by sip, never getting beyond the tipsy stage, maintaining a moderate effect of pleasant intoxication.

At six in the morning, we started wrapping up the party. I helped the host with the cleanup — and by the way, invited her to the dating show (she agreed). An hour and a half later, I headed home. And at eight in the morning I fell asleep, already sitting on a train on London underground. With phenibut, sleep is especially sweet. And no, I didn't black out. I just fell asleep on a train.

It was already Sunday. I was yo-yoing from East London to West London on the Metropolitan Line. Waking up either too far east or too far west, I would get off and board a train in the opposite direction, but each time I’d fall asleep and miss the needed station. It's kind of like pissing in a urinal when you're completely wasted — the stream goes left, then right, then left, then right. It’s just like that, but on the scale of the entire city. This is my poorly crafted punk analogy to end this punk essay.

At noon, I somehow miraculously woke up at exactly the right station — well-rested and in a great mood. I managed to jump out of the car before the doors closed. The backpack was still with me — I was holding it tight.

But I left my headphones on the train.

you seem like an interesting and fun person. i like the way you think. had a great time reading this. cheers !

this reminded me of the time i lost my passport at stansted and procrastinated on getting a new one until they emailed me two months later saying they have it..... which almost definitely taught me the wrong lesson !!!