Near-Instantly Aborting the Worst Pain Imaginable with Psychedelics

ClusterFree.org — Psychedelics for Cluster Headaches

Psychedelics are usually known for many things: making people see cool fractal patterns, shaping 60s music culture, healing trauma. Neuroscientists use them to study the brain, ravers love to dance on them, shamans take them to communicate with spirits (or so they say).

But psychedelics also help against one of the world’s most painful conditions — cluster headaches. Cluster headaches usually strike on one side of the head, typically around the eye and temple, and last between 15 minutes and 3 hours, often generating intense and disabling pain. They tend to cluster in an 8-10 week period every year, during which patients get multiple attacks per day — hence the name. About 1 in every 2000 people at any given point suffers from this condition.

One psychedelic in particular, DMT, aborts a cluster headache near-instantly — when vaporised, it enters the bloodstream in seconds. DMT also works in “sub-psychonautic” doses — doses that cause little-to-no perceptual distortions. Other psychedelics, like LSD and psilocybin, are also effective, but they have to be taken orally and so they work on a scale of 30+ minutes.

This post is about the condition, using psychedelics to treat it, and ClusterFree — a new initiative of the Qualia Research Institute to expand legal access to psychedelics for the millions of cluster headache patients worldwide.

Cluster headaches are really fucking bad

If you’ve been on the internet long enough, you’ve probably seen memes like the one above. Despite what it tries to imply, pain intensity is not really about the amount of red on a schematic — or even the size of the actual area affected.

A tension headache is just your regular headache — most people get these from time to time. A person with a tension headache can usually function, especially if they take some ibuprofen or aspirin. I get these headaches occasionally and I can easily imagine someone preferring a mild one to some CHRISTMAS MUSIC.

Migraines are much worse — there is debilitating pain that lasts for hours, often with extreme light sensitivity and vomiting on top of it. I’ve never had one, but I’ve watched someone close to me get them regularly — and I’d personally pause before wishing a migraine on my worst enemy. Our old good friends, ibuprofen and aspirin, are at least somewhat helpful for a majority of patients.

And cluster headaches are even worse than that — often far, far worse. So much worse that people often feel profoundly spiritually betrayed by the very fabric of existence, saying that they “feel betrayed by God”. Regular ibuprofen and aspirin are of no help.

Two quotes by patients (from Rossi et al, 2018)

Yves, a patient from France:

You no longer have a headache, or pain located at a particular site: you are literally plunged into the pain, like in a swimming pool. There is only one thing that remains of you: your agitated lucidity and the pain that invades everything, takes everything. There is nothing but pain. At that point, you would give everything, including your head, your own life, to make it stop.

Thomas, another patient from France:

If you want to understand what it means to live with cluster headache, imagine that someone is stabbing a knife in your eye and turning it for hours. Imagine the worst pain. Imagine a daily torture, gratuitous, incomprehensible. Imagine yourself suffering alone, terribly. Imagine being a prisoner in a straitjacket of suffering... Imagine the desire to finish, with pain, and the desire to finish … with yourself. If you imagine, you will understand

Not your regular tension headache, right? Pain like this is why cluster headaches were dubbed “suicide headaches”.

These quotes paint an extremely bleak picture of terrible suffering. But how much worse are these experiences compared to other very painful experiences, exactly? Can we quantify this?

The problem with measuring pain

Imagine you are tasked with designing a pain scale. Where do you start? This is easy: make zero be completely pain-free. Step one: done.

Step two: design the rest of the pain scale. Time to start comparing actual pain experiences with each other. Maybe we can take a common pain experience like mildly stubbing a toe and pin it to 1. A really badly stubbed toe could be a 2. So far so good: you’d rather stub your toe mildly than badly — makes sense.

Then you need to place varied pain experiences on the scale: chronic back pain, extracting a tooth without anaesthesia, breaking many bones in a car crash, and others. Now this is getting tricky. And finally, where do you put “pain so bad you feel spiritually betrayed by the very fabric of existence” which is what cluster headaches are often described as?

Maybe you are thinking: “Alright, you convinced me it’s not that easy. I’m just going to cheat by looking at what the medical profession came up with.” Fair enough, but the answer we get from the medical profession is to just (1) cap the scale at some number and (2) give people vague questionnaires.

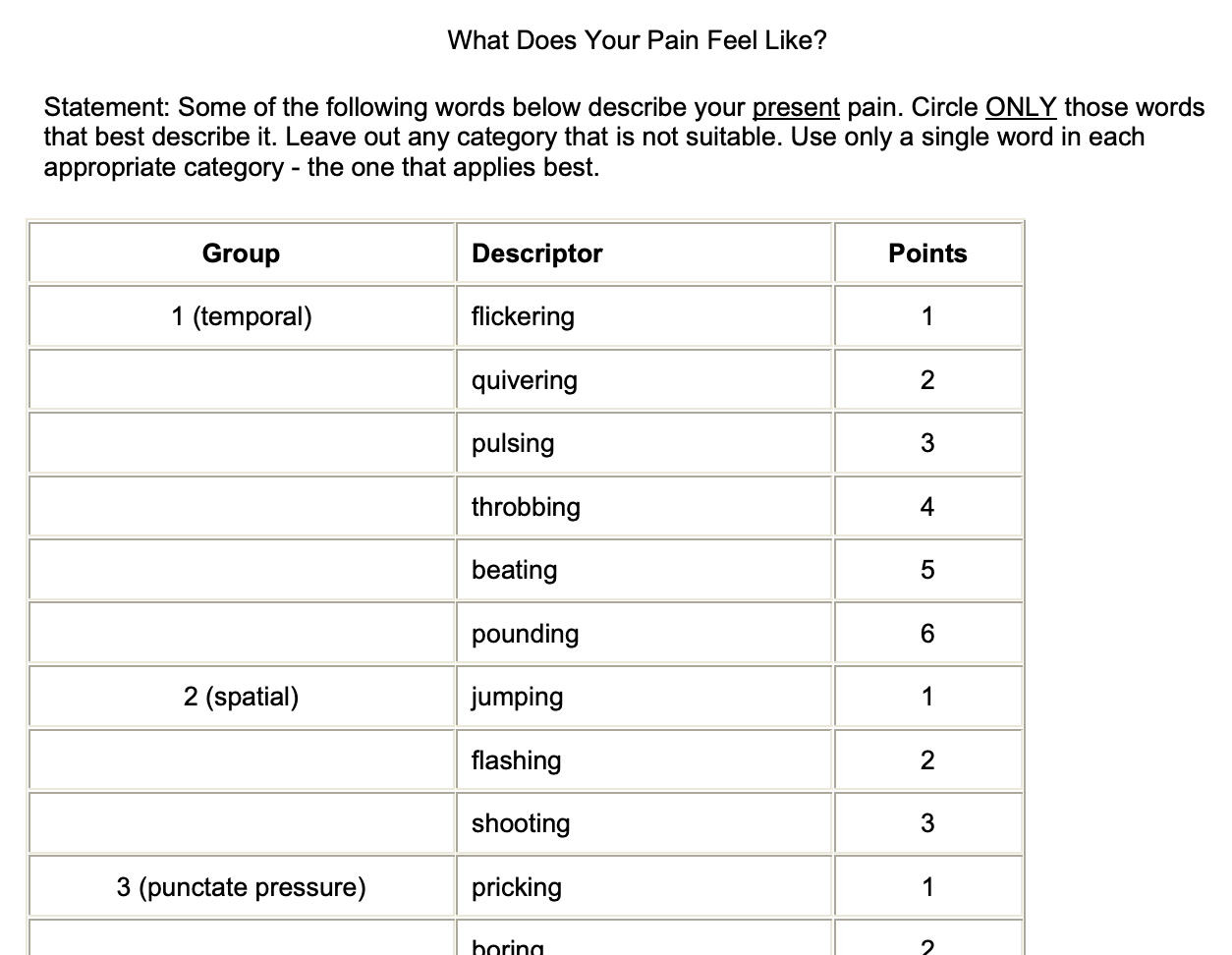

The McGill Pain Questionnaire

The above is an excerpt from a commonly used tool, the McGill Pain Questionnaire.

The McGill Pain Questionnaire caps its scale at 78. It asks people to apply a bag of words to their pain giving a score of 1–6 to each label — the scores are then summed into a final one. “Sharp throbbing flashing pain that terrifies you” would be 10/78 (assuming no other adjectives apply to it).

While this scale is multi-dimensional, it does not exactly “carve reality at its joints” — it doesn’t provide us with actual insight into the nature of pain and the substrate that generates it.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s still useful, especially in the medical context. You can track a patient’s improvement over a period of time. And if one day’s “27” is actually better than another day’s “26”, that’s still fine as the overall trend over days and months is informative. You can adjust treatments and use the score as a rough guide — some “measurement noise” is fine.

But we can’t trust a scale like this to give us a trustworthy estimate of how much worse cluster headaches are compared to other high-pain experiences.

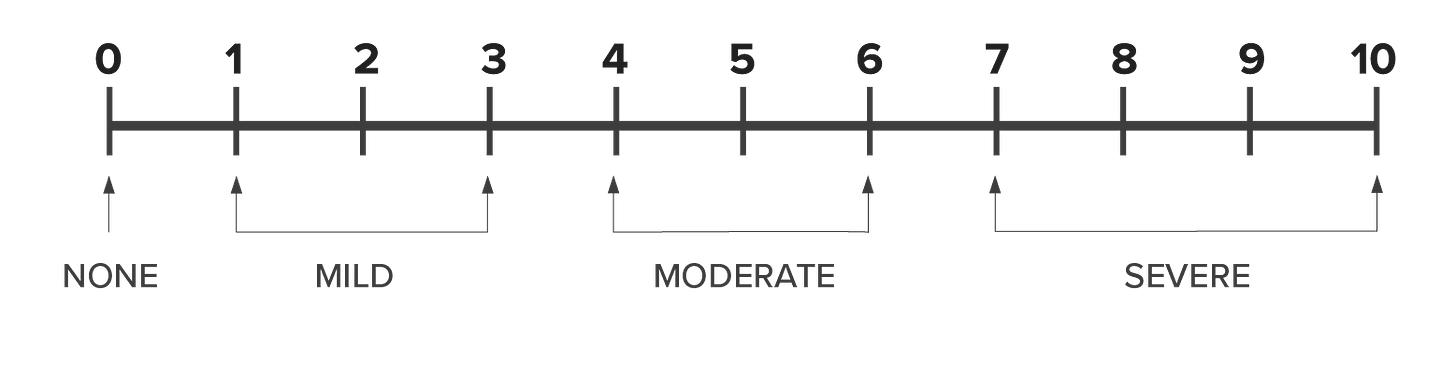

The 0–10 Numeric Rating Scale

Sometimes scientists take an even simpler approach. We’ve all had a number of varied pain experiences throughout life — and we can rank them roughly. Why apply a bag of vague words with arbitrary scores when you can just ask people to put a number on their experience?

That’s the idea behind the 0–10 Numeric Rating Scale — one of the most widely used pain scales in clinical care and research. This scale asks people to assign a number from 0 to 10 to their experience, with 0 being “no pain” and 10 being “the worst pain imaginable”. Pretty reasonable, right?

One problem with this pain scale is illustrated in this xkcd comic strip. The “worst pain imaginable” requires you to extrapolate features of your current experience to some imaginary ceiling. This extrapolation might be different for different people. And there is no a priori reason for your imagined ceiling to be the true physiological pain max.

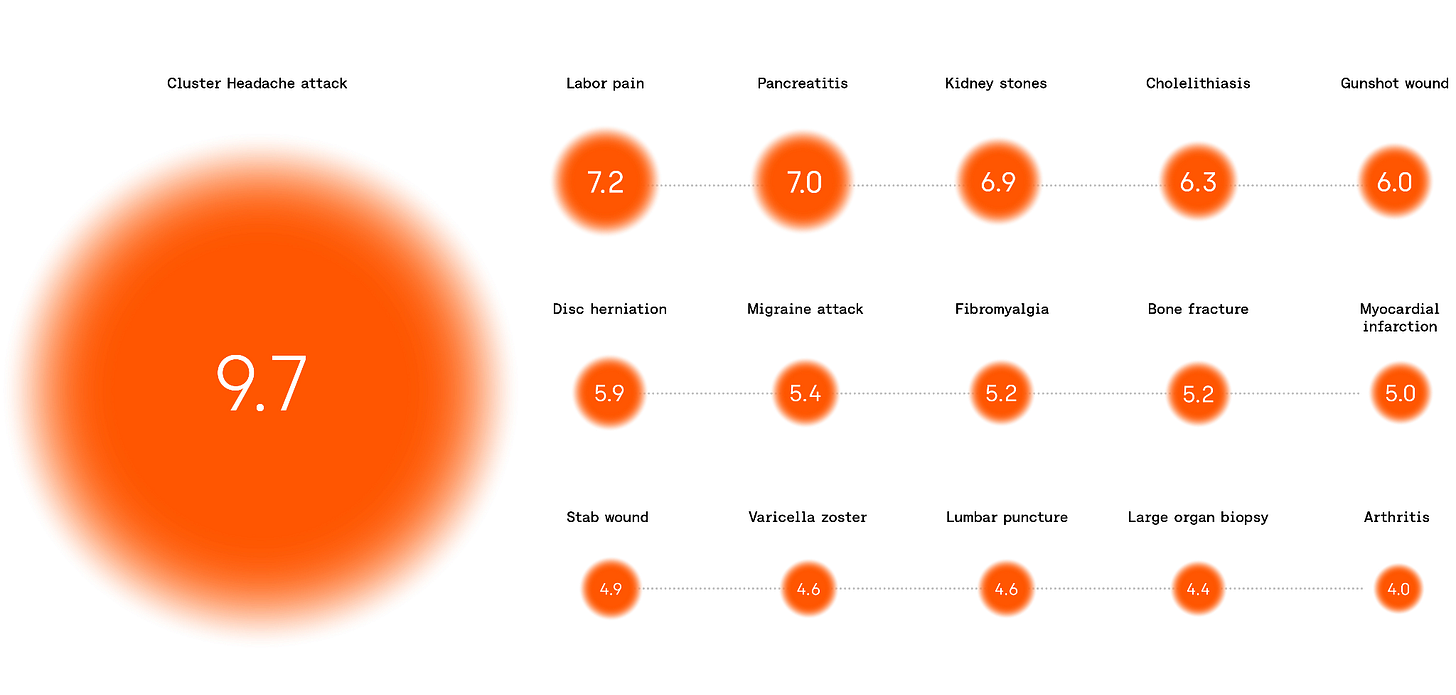

Still, empirically this scale provides some useful signal that allows us to compare experiences, even if imperfectly — by averaging out individual differences. Cluster headaches frequently get rated at 10 on this scale.

The heavy tails of pain (and pleasure)

There is another big problem with mapping pain onto an arbitrary numeric scale, such as 0–10. The 9.7 pain is not twice as bad as 4.85 pain — it’s orders of magnitude worse.

There is no built-in objective “pain counter” in the human mind. When people report a number, their mind has to compress a multi-dimensional internal state into a single scalar estimate.

This compression ends up being logarithmic due to Weber’s law:

Weber’s Law describes the relationship between the physical intensity of a stimulus and the reported subjective intensity of perceiving it. For example, it describes the relationship between how loud a sound is and how loud it is perceived as. In the general case, Weber’s Law indicates that one needs to vary the stimulus intensity by a multiplicative fraction (called “Weber’s fraction”) in order to detect a just noticeable difference. For example, if you cannot detect the differences between objects weighing 100 grams to 105 grams, then you will also not be able to detect the differences between objects weighing 200 grams to 210 grams (implying the Weber fraction for weight perception is at least 5%). In the general case, the senses detect differences logarithmically.

(From Logarithmic Scales of Pleasure and Pain: Rating, Ranking, and Comparing Peak Experiences Suggest the Existence of Long Tails for Bliss and Suffering by Andrés Gómez-Emilsson).

An intuition for Weber’s law for pain

The above picture is an illustration of Weber’s law from Wikipedia. Both columns have 10 more dots in the bottom square than in the top square. But the absolute difference is much easier to detect on the left than on the right, because the relative difference is larger.

Now imagine “units of pain” in one’s experience. The difference between 10 units and 20 units would be perceived clearly. But 110 and 120 units would seem almost the same — despite the same absolute difference in pain.

Detecting a step increase on a linear scale requires the underlying experience to increase by a multiplicative factor. And so a pain scale like the 0–10 Numeric Rating Scale ends up being logarithmic — with the underlying experience varying in intensity by orders of magnitude.

This section is only meant to provide an intuition — the full argument is more complex and outside the scope of the current post. I recommend reading the already-linked “Logarithmic Scales of Pleasure and Pain” by Andrés Gómez-Emilsson. It combines conceptual models with phenomenological accounts from meditation, psychedelics, eating spicy foods and even getting bitten by various insects.

That article makes another important claim. Traditionally people interpret Weber’s law as a compression that happens in your senses, in early stages of processing stimuli. That may be happening for things like dots in the visual field or sound, but for internal feelings like pain, the feeling itself follows a long tail. Precisely because we can’t estimate small differences when the internal sensation is so high, the sensation needs to change by a certain constant multiplicative factor for your internal estimation to be able to confidently say “ah, this hellish pain increased still a bit further”.

Why adequately quantifying pain matters

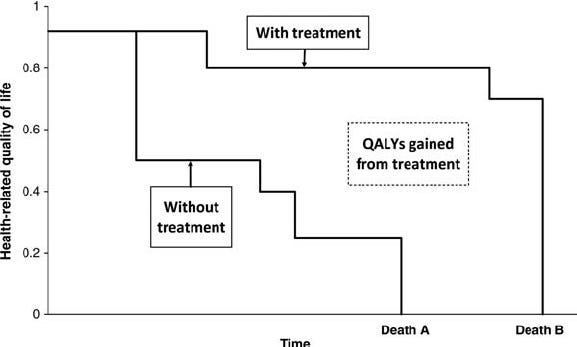

The medical field’s major metric for allocating resources is the QALY — quality-adjusted life-years. QALY has two anchor points: 1.0 (perfect health) and 0.0 (dead). It combines two different categories — length of life and the quality of it — into a single score.

To compute it, you multiply a patient's health-state score by the time spent in that state — so one year in perfect health is 1.0 QALY, one year at half quality is 0.5, and so on. The health-state score comes from standardised questionnaires that rate things like mobility, pain, anxiety, and self-care.

QALY as a metric kind of makes sense. Ideally you want your patient to be perfectly healthy, functional, and live long. A patient being non-functional and suffering for some time results in a drop in the metric. As does a patient dying early.

Some health states are deemed worse than death, which yields negative scores. This is reasonable and good, but those negative scores are capped at slightly below zero — the two common instruments bottom out at -0.281 and -0.594. And so extreme suffering ends up being compressed into at most a modest negative penalty on this metric — relative to other, less painful, conditions.

The QALY metric ends up as an input into many economic calculations for deciding whether resources should be allocated for this condition vs that one. And so the extreme suffering of cluster headaches gets a modest boost in funding at best relative to similarly disabling conditions with only modest pain.

Ideally, we need some kind of a qualia-adjusted life-years — a metric that takes into account the actual phenomenology of people’s experiences. In the absence of such a metric, cluster headaches and other conditions of extreme suffering are overlooked and underfunded.

Treating cluster headaches

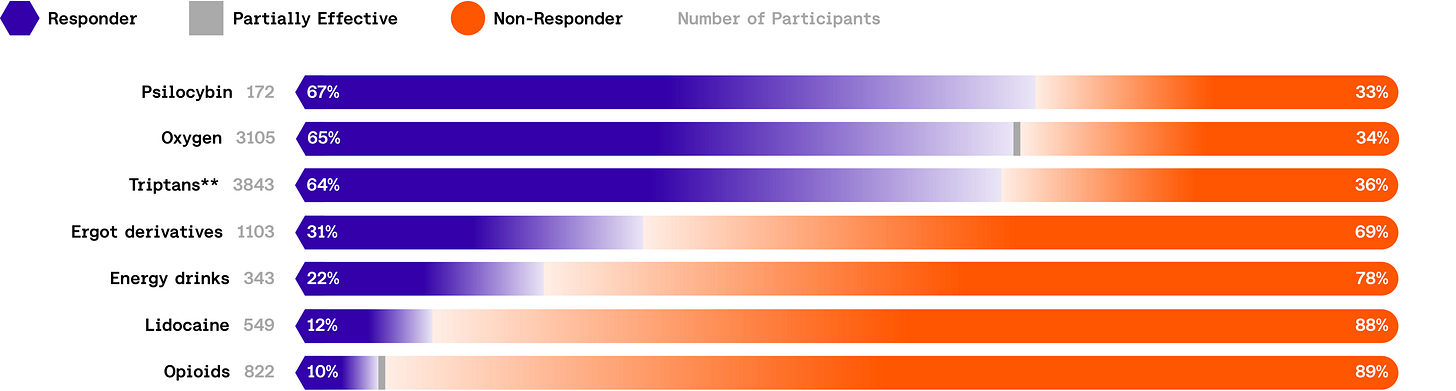

The two most commonly used treatments for cluster headaches are high-flow oxygen and a class of medication called triptans (particularly sumatriptan). They are quite effective — 60-80% of patients respond to either option.

But they also have problems.

Oxygen tanks are difficult to carry around, which limits their effectiveness when an attack hits suddenly. And even when one is available, it can take 10–15 minutes of breathing oxygen to stop an attack — with the patient being in severe pain the whole time.

Triptans are very much a double-edged sword. Short-term, they help with attacks, but long-term, their repeated use can actually make attacks last longer, become more numerous and more painful.

Psychedelics are the most effective treatment

The above chart shows that a classical psychedelic, psilocybin, is more effective than the two usual recognised treatments — oxygen and triptans. And there is now emerging evidence that another psychedelic, DMT, is even more effective than psilocybin.

Vaping DMT allows it to enter the bloodstream in seconds — it starts working near-instantly, faster than any other treatment. Unlike triptans, it doesn't produce tolerance — you can just keep taking it without it losing its effectiveness.

And despite what the label “psychedelic” might imply, it’s effective in “sub-psychedelic” doses — doses that cause almost no perceptual distortions. Aborting an attack does not require meeting DMT elves or experiencing other crazy effects that high doses are famous for.

Because DMT is so fast-acting, patients can easily titrate it: take a puff from a vape pen, wait 30 seconds, take another puff — until the attack is gone completely, and before DMT’s psychedelic effects kick in. DMT has a very short half-life of 5–15 minutes, so even if you accidentally overdid it, you’d only need to wait a few minutes for the psychoactive effects to subside.

A DMT vape pen is your regular vape pen — just with DMT instead of nicotine. It’s easy to carry around as an emergency “get out of hell” device. Bob Wold, president of Clusterbusters and a cluster headache patient who’s tried over 70 different treatments (almost all ineffective), describes DMT in an interview on YouTube:

One inhalation [of DMT] will end the attack for most people. Everybody is reporting the exact same thing. […] It could end that attack in less than a minute. […] You can take one inhalation, you can wait 30 seconds, and if that cluster is not gone completely, then you know it’s time to take another inhalation. You don’t have to wait 2h into a psilocybin trip.

[…]

You can actually visualise a switch being shut off in the middle of your brain. I hear a click as the switch is shut off and the pain is completely gone. It doesn’t, you know, slowly go away. It’s a switch that shuts it off completely.

LSD and psilocybin are also helpful, but they take a while to kick in, so they are less immediately useful for aborting a sudden attack. Many patients use them preventively during a cycle — there are protocols involving dosing them every 5 days or so.

To learn more about the pros and cons of various treatments, including DMT, read “Emerging evidence on treating cluster headaches with DMT”, by Alfredo Parra.

Why psychedelics help with cluster headaches

We don’t have a complete mechanistic story for why psychedelics help. It’s clear that the usual perceptual and emotional changes are not key here — for cluster headaches, you take psychedelics in lower “sub-psychedelic” doses.

We also don’t know if there is a single root cause for cluster headaches — our story for how they happen is incomplete. The usual explanation: cluster headaches are a “clock + wiring” problem in the head.

The “clock” is the hypothalamus. It is a small, deep brain region that helps run the body’s daily rhythms (sleep/wake timing, hormones, temperature). In cluster headaches, this internal clock seems to get stuck in a pattern where it repeatedly primes the system for attacks at similar times each day, and sometimes in certain seasons.

The “wiring” is the trigeminal nerve — a big nerve that carries sensations, including pain, from the face, eye, teeth, and parts of the head into the brain. Think of it like a high-speed cable that reports “something is wrong” from the face and head. When an attack hits, this cable becomes intensely activated on one side, producing the severe, drilling pain around the eye and temple.

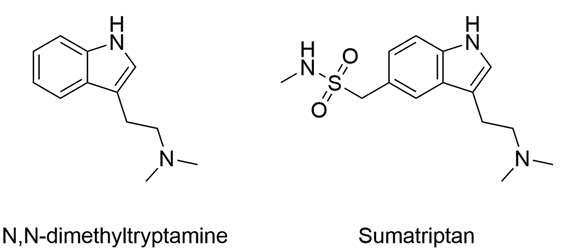

Both of these areas are rich in serotonin receptors. Psychedelics are serotonin agonists — they resemble serotonin and bind to the same receptors. If a cluster headache attack is a mis-timed, over-excitable network, a strong serotonin “signal” might temporarily change the network’s set-point, calming it down.

Triptans, a class of medications mentioned in the previous section, are also serotonin agonists. The most commonly used medication of this class, sumatriptan, acts as a serotonin 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and 5-HT1F receptor agonist. DMT has a different profile: it’s an agonist at 5-HT2A (the receptor most associated with classic psychedelic effects) and also shows agonism at 5-HT2C and 5-HT1A. The pharmacology of these compounds is quite different — but they affect the same underlying system. So it’s not that surprising psychedelics work for cluster headaches — even if the usual “psychedelic” effects we associate with these compounds are not involved.

Fun fact: sumatriptan is a DMT derivative, in a literal sense. Its chemical formula is 5-(Methylsulfamoylmethyl)-DMT — basically, DMT with an extra chunk attached. And while that chunk significantly changes the pharmacology (as described above), DMT is not some alien molecule with no resemblance to existing medicines — it’s a chemical cousin of one.

The full story of DMT action is likely more complicated: for example, DMT also activates the sigma-1 receptor, which reduces inflammation and interacts with pathways in the hypothalamus.

Bob Wold, president of Clusterbusters and a cluster headache patient, whose quote appeared in the previous section, has an even spicier theory of DMT action. Here it is: DMT is an endogenous compound, produced by many mammalian brains (including human ones) and cluster headaches are caused by a dip in endogenous DMT levels. I’m not sure I buy it — it doesn’t really explain why levels would drop or how that would cause headaches. But the fact that a patient reaches for a theory like this at all is a testament to how dramatic DMT can feel as a treatment.

ClusterFree

Millions of cluster headache patients worldwide are trapped in extreme, disabling pain — repeatedly, often multiple times a day, for prolonged periods of time. During attacks, people often can’t sit still, can’t work, and can’t think about anything except the pain. Between attacks patients experience PTSD-like symptoms, anticipating their return — a sort of “current traumatic stress disorder”.

Psychedelics provide effective pain relief for cluster headaches. DMT in particular aborts attacks near-instantly — in seconds.

And yet, most cluster patients worldwide lack access to these treatments. Those who obtain access do so by breaking the law — with potentially severe legal consequences in many jurisdictions (case in point).

ClusterFree is a new initiative of the Qualia Research Institute to expand legal access to psychedelics — and solve this ongoing crisis. ClusterFree was started in late 2025 and aims to:

— Publish open letters demanding that governments, regulatory bodies, and medical associations worldwide take action immediately.

— Engage with policymakers globally to advocate for better access to treatments.

— Publish research on cluster headaches and support other researchers in the field.

— Collaborate with entrepreneurs and philanthropists motivated to bring effective treatments to market.

ClusterFree is co-founded by Dr. Alfredo Parra (twitter) and Andrés Gómez-Emilsson (other blog and twitter). Both of them have been doing relevant work for many years — I’ve been linking to it throughout the post and I’ll provide more links at the end of this post.

I reached out to Alfredo Parra to learn ClusterFree’s near-term plans are — here is his response:

We’re going to publish an authoritative, multilingual guide on how to safely use DMT to abort cluster headaches, which will be extended over time to include other treatments.

We’re reaching out to journalists in the UK to run stories about cluster headaches (in particular the underground use of DMT).

We’re reaching out to MPs in the UK to demand increased research funding and compassionate access to scheduled substances.

You can help solve this medico-legal crisis

You've just read what cluster headache patients go through. Most of them can't legally access the treatments that works best. You can help ClusterFree change this.

Sign a global letter

The letter is already signed by over 1000 people, including many notable ones, such as Scott Alexander and Peter Singer — you can see their signature at the end. My signature is there too. It takes a minute to add your signature there.

You can also sign a national letter — if you are in one of the following countries: Australia, Brazil, Canada, Germany, Mexico, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States. My signature is on the UK one.

These letters aren’t just for reaching policymakers in power. They are also a way to reach prominent people, find volunteers and collaborators, encourage other people to start projects and overall legitimise the cause area by showing that a lot of people care about it.

Donate

ClusterFree.org has already raised $107k+ in donations during their End of Year Fundraiser 2025. This allowed them to set up basic organisational infrastructure and fund Alfredo Parra’s full-time work on the project.

The current funds have also allowed to hire a part-time person to help with various projects, primarily outreach and communications. The aim is to raise $150k — the extra $43k would allow ClusterFree to hire that person full-time for at least a year.

Every dollar donated will go towards averting extreme suffering by patients of a condition that’s overlooked and underfunded because of how metrics like pain scales and QALY compress experience. This is one of the rare problems where a relatively small amount of money, effort, and political pressure can end a large amount of suffering.

Hell must be destroyed

Sometimes people say that pain is a meaningful feedback mechanism. While this is often true, in cluster headaches the mechanism goes haywire, trapping millions of people in torturous hell on earth.

There is no lesson in cluster headaches: no growth, no silver lining, no meaning. The nervous system misfires and a human being is tortured for hours — then it happens again and again.

This hell must be destroyed. We have the tools for this — but the laws won't let people use them. Laws change when enough people demand it. If you want to help ClusterFree, you can — with your signature and money.

Links to articles

Logarithmic Scales of Pleasure and Pain: Rating, Ranking, and Comparing Peak Experiences Suggest the Existence of Long Tails for Bliss and Suffering by Andrés Gómez-Emilsson

An academic article, “The heavy-tailed valence hypothesis: the human capacity for vast variation in pleasure/pain and how to test it” by Andrés Gómez-Emilsson and Chris Percy

Emerging evidence on treating cluster headaches with DMT by Alfredo Parra, Curran Janssens and Andrés Gómez-Emilsson

Quantifying the Global Burden of Extreme Pain from Cluster Headaches by Alfredo Parra

12+ Reasons to Donate to ClusterFree by Andrés Gómez-Emilsson

Cytokines and Migraine: How Inflammation Drives Pain and How Psychedelics May Modulate It

How much should we value averting a Day Lived in Extreme Suffering (DLES)? by Alfredo Parra

ClusterBusters — a charity run by Bob Wold

Links to videos

DMT for Cluster Headaches: Aborting and Preventing Extreme Pain with Tryptamines and Other Methods — an interview with Bob Wold, Joe Stone, and Joe McKay

The Case for DMT for Cluster Headaches: Practical Tips & Why It Deserves Urgent Scientific Attention by Andrés Gómez-Emilsson

Alfredo Parra’s talk on the topic below

As a third French guy with cluster headaches, I can tell you the others make me doubt the validity of pain scales, because I don't think I would describe my pain in the same way as the others

I am probably lucky in that my attacks are less severe than this, but I also can't shake the feeling that maybe they're better at compelling descriptions

Also, a big part of suffering for me is the rational fear of future disability, and cluster headaches don't bring that

Anyway, I can abort my crises with a few minutes of intense cardio, which confirms that they are not that intense apparently:

https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.52263

https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint16060123

And I haven't had a crisis in more than a year, hopefully they won't come back!

This is extremely important work I was unaware of, thank you for sharing.